Extending fields spread flatly, far to either side, uninterrupted to the sight, not any longer barriered nor revetted in. It was a great goodness in their eyes, this expanse, they drank in this visual freedom gladly, and were disposed to linger before dropping one by one down … (In Parenthesis, Part 4)

It is refreshing when you encounter an uninterrupted view across a landscape. Imagine what such a view must be like after you have seen nothing but a wall for months on end. Soldiers during the First World War spent long months with their gazes confined by trenches, barriers and the threat of sniper fire.

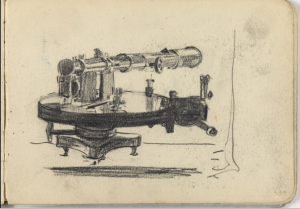

The acclaimed poet and artist David Jones was one of those soldiers – born in London in 1895 of a Welsh father and English-Italian mother. He was the longest serving British soldier recognised as a war poet, quite incredibly spending most of his time in the trenches.

Jones is best known for his long poem In Parenthesis (1937). The poem tells the story of an infantryman, Private John Ball, whose battalion leaves a training camp in England for France. The soldiers move up into frontline trenches at the edge of a wood. The tension then mounts as they prepare for battle. The poem concludes with an advance against the German lines in which most of the soldiers are wounded or killed.

Jones’ poetry was grounded in a search for what lies beyond appearances. In the Preface to In Parenthesis, Jones noted: “We find ourselves privates in foot regiments. We search how we may see formal goodness in a life singularly inimical, hateful, to us.”

It might seem a stretch to suggest that life in school for pupils can be singularly inimical, hateful, to them. However, many pupils do experience a sense of oppression at school, feeling barriered and revetted in. An entire lexicon – with accompanying practices – pertains to constraints in schooling: detention, gates, deadline, penalty, discipline, lines, punishment, suspension, expulsion, exclusion, rules and so on. One does not always think of a school as a place of joy, discovery, and the development of human potential.

It is intriguing that Jones himself made a connection within In Parenthesis between being free from school and possessing a heart at ease. In Part 4 of the poem we see Ball on sentry duty, looking across at the wood where the Germans are encamped:

Across the very quiet of no-man’s-land came still some twittering. He found the wood, visually so near, yet for the feet forbidden by a great fixed gulf, a sight somehow to powerfully hold his mind. To the woods of all the world is this potency––to move the bowels within us.

To groves always men come both to their joys and their undoing. Come lightfoot in heart’s ease and school-free; walk on a leafy holiday with kindred and kind; come perplexedly with first loves––to tread the tangle frustrated, striking––bruising the green.

Are there any hints in his writing about how one’s heart might be at ease, even in school?

The poem In Parenthesis was dedicated to one of Jones’s friends who died during the war. Those who advance together on the German lines are mates, whether they are ‘men of the stock of Abraham from Bromley-by-Bow’, ‘Anglo-Welsh from Queens Ferry’ or ‘rosary-wallahs from Pembrey Dock’. A ‘wallah’ is an Indian word for a person with a particular duty – hence this description of Irish Catholics.

At the climax of the battle, Private Ball is prevented from mourning the loss of a comrade who has just died in his arms. He is commanded to return to his digging of a trench, but this cannot prevent him from grieving in his heart even as he recognises that his mate will be buried beneath the bodies of others. Ball’s own experience of the battle concludes when he is himself wounded. Private Ball’s heart might not have been at ease, but it is certainly portrayed as full rather than empty at that point in time, in a portrayal that draws deeply on Jones’ own experience of the war.

What difference would it make if schools were to invest as much energy in fostering friendships between pupils, and companionship between pupils and teachers, as in enforcing discipline and hitting targets?

Jones, David (1937) In Parenthesis, Faber and Faber: London

The full text of In Parenthesis is available online at: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.13580/page/n3/mode/1up

Dr Peter Kahn is Director of the Centre for Higher Education Studies at the University of Liverpool. He curated an exhibition on the poetry and art of David Jones at a cultural event in London that was held 100 years after the end of the First World War.

https://thelondonencounter.co.uk/freedom-in-the-trenches/